The World Is Flat, Except When It Isn’t

The Yin and Yang of Globalization and Deglobalization

By James A. Tompkins, Ph.D., Chairman, Tompkins Ventures

October 2023

Executive Summary

Humans have engaged in commerce for millennia. From the first moment Uruk exchanged a hunk of charred meat for extra-sharp spears from Grok, living standards have improved when people specialize in producing goods and services and trade the surplus.

That trade has grown from areas that encompass villages to regions to nations to the entire planet. Early evidence of international trade dates to the Sumerians in the third and fourth millenniums B.C., with routes ranging from Pakistan to the Persian Gulf to west of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers.[1] By the 1980s, academics started applying the term “globalization” to the growing integration of economies around the world.[2]

Increasingly, globalization referred to single-sourced, low-cost supply chains that relied heavily on China for raw materials, parts and/or finished goods. The Great Recession of 2007-2009 and snarled pandemic supply chains gave the term globalization a bad name. Now, tariffs, trade wars, shooting wars and political and consumer pressure are forcing enterprises to reorient production and supply away from China and other nations viewed as unfriendly.

This “deglobalization,” I would argue, is happening at the same time as further globalization – the integration of economies continues, albeit in different regions and at different speeds. This simultaneous yin and yang of globalization/deglobalization results in even more disruption in an age where disruption is the new normal.

To succeed in this new arena for 2024 and beyond, leaders will have to:

- Redesign global supply chains. This goes beyond final assembly to your entire global network – sourcing, production, suppliers, distribution.

- Deploy optionality as never before, considering multiple alternate production, logistics and transportation solutions.

- Examine the potential to develop nearshoring logistics hubs, such as the Dominican Republic for the Western Hemisphere.

Many executives never gave their supply chains a second thought until the pandemic. They might consider leaving China a supply chain redesign. That is a short-term impossibility. Nor does supply chain redesign just mean reshoring, nearshoring or friendshoring.

Instead, redesigning supply chains will require the full range of optionality, the global network of sourcing, production, suppliers and distribution described above. Optionality also includes access to technological innovations that enable digital supply networks, along with vetted and trainable workforces in new countries and regions.

You must redo your transportation providers, your distribution/fulfillment/

3PL providers and plan for the right technology to allow seamless end-to-end supply chain execution. This execution must go beyond your enterprise to include every partner that handles every part of your supply chain, from raw materials to final mile delivery.

Such redesigned supply chains are the only way enterprises will be able to navigate the shifting and evolving political realities and consumer expectations that define our age of perpetual disruption.

That perpetual disruption will require continued adjustments – redesigning global supply chains is not a one-time activity.

The sooner business leaders grasp the insight that any new normal will soon be swept away, the sooner they can become insightful leaders. The future will continue to be a departure from the past, not a continuation. Creating competitive advantage from now on involves using insight to specify shifts that provide opportunities, harnessing the power of those insights to identify obsolete paradigms, discovering innovations that will replace those paradigms and deploying those insights and innovations to disrupt the status quo.

Contents

The World Is Flat, Except When It Isn’t 0

The Yin and Yang of Globalization and Deglobalization 0

Globalization vs. Deglobalization 2

The Yin and the Yang of Globalization 5

The Evolution of Supply Chain 7

The Container Revolution and Supply Chain Hubs 9

The Dominican Republic – The Hub of the West 12

The Necessity of Technology 14

Natural Resources – The World Is Your Supply Depot 15

Government, Global Supply Chains and Globalization 22

A Level Playing Field? Hardly 28

Impacts On Your Supply Chain: A Call to Action 31

Conclusion: The Reorientation Is On 34

Globalization vs. Deglobalization

Is globalization dead? Or is deglobalization dead?

Sound arguments can be made for both. Each side cites statistics on exports plus imports as a proportion of national income, migration flows weighted by population, capital investment as a portion of national income and more. We can see this playing out in real time as Chinese exports are down. On the other hand, trade between the U.S., Mexico and Canada are at an all-time high.

Clearly, something is going on. However, the truth lies somewhere in the middle – globalization and deglobalization are alive and well, existing simultaneously, waxing and waning in different areas of the planet at different times. It all depends on your view. Globalization can be increasing between countries in Asia while deglobalization is increasing between China and the United States. Globalization can be increasing among European countries in the Schengen continental area while deglobalization (Brexit) is increasing between those countries and Great Britain – all at the same time.

Confused? Well, think about how this VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity) fouls up global supply chains. Tariffs here, free trade agreements there, subsidies for preferred businesses in some places, punitive tax policies elsewhere, trade restrictions on various exports elsewhere. More than ever, successful enterprises will deploy optionality – moving away from single, low-cost sourcing to multiple sources for raw materials, parts and finished goods. Developing agile supply chains that source from multiple companies, countries, continents and hemispheres. Optionality can help transform the yin of VUCA – volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity, which hamper your organization’s ability to serve customers and grow – into the yang of VUCA – vision, understanding, clarity and agility, which help pave the way toward profitable growth and competitive advantage.

The retreat from globalization has divided the world into multiple regions. One power bloc encompasses China and its allies, including Russia. The United States and the European Union and their NATO allies head up another power bloc. Other largely Democratic Asian countries and regions are aligned with this bloc. They include Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand. Other non-aligned countries, such as India, will cooperate with each bloc based upon their self-interests and national goals.

For the last 20 years, China has pushed many policies that trigger deglobalization. True, the Communist country has become integrated into world trade, transformed itself into the factory of the world and initiated a massive Belt and Road Initiative to connect China on new “Silk Roads” to Asia, the Middle East and Europe. But the country has routine trade barriers that include tariffs, import restrictions and requirements that companies both form joint ventures with Chinese companies and turn over technology to China.

The United States, especially, has added to that push for the last 10 years, with Europe joining in sanctions on Russia after its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. So, most signs in 2023 point toward deglobalization. This is a stark contrast to the last 143

Except for two periods of deglobalization (1930s and 2010s), globalization has increased since 1880.

Peter a.g. van bergeijk, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>,

via Wikimedia Commons

But let me take a step back and fill in a few basics:

- What is the definition of globalization? Globalization refers to the interdependence of economies, cultures and populations.

- What is the definition of deglobalization? Deglobalization is the movement toward a less-integrated world, characterized by local solutions, onshoring, tariffs and border control.

- Decisions about globalization vs. deglobalization traditionally have had a lot to do with the costs associated with providing goods to markets.

- Comparative advantage or specialization goes back to the beginning of civilization. Once we got beyond hunter-gatherer status, five families may have lived in a community. Instead of all five individual families farming, hunting, building infrastructure, making clothes and preparing meals, each family handled one of these tasks for the whole community. Quality of life improved. As the community grew and prospered, higher levels of economies of scale came into play, and the quality of life improved even more – reaching beyond the village to the county, the region, the state/province and eventually into international trade.

- Comparative advantage has evolved into a key concept in globalization and international trade. Trade benefits a country’s population because specialization allows certain countries, cities, regions or factories to specialize and produce more of a certain type of good or service. Trading from such abundance means people can increase consumption and raise their standard of living. Clearly, deploying comparative advantage and globalization are net positives when done on a level playing field. Or, with apologies to The World is Flat author and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Thomas Friedman, globalization is marvelous if the world is flat (has a level playing field).

- Globalization has many effects on comparative advantage and international trade, such as:

- Globalization increases the size and diversity of the markets that countries can access, which creates more opportunities for trade and specialization based on comparative advantage. So instead of five families in a community, maybe 500 companies in a state, 50,000 companies in a country or 50 million companies in the world are all increasing quality and economies of scale.

- Globalization reduces the barriers to trade, the tariffs, quotas, subsidies and regulations that create an unlevel playing field. Such barriers distort comparative advantage and incentivize inefficient resource allocation.

- Globalization increases competition and innovation among companies, which can enhance or erode their comparative advantage over time.

- Likewise, globalization can either enhance or diminish a country’s comparative advantage over time. Therefore, it is important that countries adapt to the changing global environment and pursue strategies that maximize benefits from globalization while minimizing their costs.

- That said, overall, globalization during the last few decades was a global good: 2 billion people lifted out of poverty,[4] soaring global economic growth, innovative companies emerging from parts of the world they had not before. The price? In the U.S. and elsewhere, local economies, jobs and cities suffered from the abrupt changes. The lesson is that globalization also requires foresight and action to mitigate the hardships experienced by some people, industries and localities.

- Globalization is not dead, nor is deglobalization dead. Both are alive and living, evolving and changing daily. Globalization and deglobalization continue to respond to changes in the levelness of the playing field (duties, tariffs, restricted markets, quotas), to world events that affect global trade and to changes in understanding the total costs related to globalization. Globalization and deglobalization are very much involved in a synchronized dance as history unfolds. Any claim that either is dead is just an observation at a moment in time for a specific scenario.

- Optionality in product sourcing diversification, including nearshoring/

friendshoring/reshoring, is a strategic imperative for future competitive advantage. Multiple suppliers for the same products and resources spread the risk and enable your operations to handle disruption and still serve customers. Bringing production and supply chains closer to your customers can cut lead times and inventory carrying costs. The potential also exists for faster cash-to-cash cycles.

The Yin and the Yang of Globalization

Nearly two decades after his book The World is Flat, Thomas Friedman continues to argue that globalization never will go away. In an interview before the 2022 World Economic Forum[5] in Davos, he noted that commentators sounded the death knell of globalization after the 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, after the 2007-2009 Great Recession – and they’re still predicting doom.

The yin and yang of globalization and deglobalization.

Image created via Bing Chat Enterprise

Yet countries and people are connecting more than ever before. Yes, globalization may have a bad name among many people whose livelihoods have been affected by job displacement, outsourcing and the shift to low-cost manufacturing in Asia. And many politicians are acting on that frustration and anger. However, as Friedman noted, in previous centuries, only countries and major companies acted globally. These days, individuals act globally with the power of countries, companies and institutions. In the first weeks of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Airbnb users rented rooms in Ukraine to the tune of $20 million, transferring aid to that country, Friedman told Davos, “before USAID had laced up their shoes.”

Friedman continued:

“Here’s a newsflash: People want to connect – it’s wired into us. And the technology every month makes it easier to connect. … Globalization is wired into us as human beings.”

The theme of Friedman’s The World is Flat, that advancing technology upgrades the power of the individual to “reach farther, faster, deeper, cheaper, in more ways and more days around more themes and subjects for less money than ever before as an individual,” continues today.

Academic and investment strategist Michael O’Sullivan is, among others, one of those who continually sound the demise of globalization. His 2019 book The Levelling: What’s Next After Globalisation makes the case for a multipolar new world order. As he told The Economist,[6] he sees those poles centered in America, the European Union, a China-centric Asia and perhaps India, depending upon how the subcontinent develops.

These regions will approach economics, freedom, war, technology and society in different ways, O’Sullivan said. Countries outside those three or four poles will struggle to find their place, and international institutions like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization “will appear increasingly defunct” – a notion that recalls the quip by Friedman about how long it took USAID to send aid to Ukraine. (In fairness to the USAID, it wasn’t that long. Agriculture, energy and medical assistance[7] started flowing the month after the war commenced.)

So, who is right? Well, going back to the third paragraph in the earlier “Globalization vs. Deglobalization” section, both are. People are connecting across the globe and acting with the power of corporations and governments. While some nations are retreating into great power competition (deglobalization), others are increasing the interdependence of their economies, cultures and populations (globalization).

Depending upon how it develops, India could rise to become the next China. I can see India pursuing globalization with economies in the Americas and across East Asia, including China, all while China and the U.S. continue tariffs, export restrictions and other trade war aspects (deglobalization).

This, obviously, plays havoc with supply chains, making optionality a necessity for future profitable growth.

But optionality is no easy thing. Globalization/deglobalization is a complex topic with continuously moving parts, and you cannot just pick up the phone and order minerals and cotton from Africa, shoes and furniture from South America and semiconductors from the ASEAN nations. You must build entire supply chains from scratch in multiple countries, continents and hemispheres. And your success will be affected not only by the history and evolution of supply chains and economics, but by access to natural resources and adequate workforces, all shaped by politics.

The Evolution of Supply Chain

For logistics professionals, the term “supply chain” came into vogue in the early 1990s. Back then, the entire concept was cost reduction. This started supply chain along its evolution from “efficiency” to “effectiveness” to “respect” to “resiliency” – EERR.

For the first E, efficiency, professionals applied supply chain strictly to internal corporate operations: Planning people talked to salespeople who talked to procurement people who talked to manufacturing people who talked to distribution people. Reaching out beyond your organization – whether you produced consumer packaged goods, parts, raw materials or a combination, was almost an afterthought. Supply chain pros aimed to find the lowest piece price at any source while reducing delivery times, production times, missed deliveries, transportation costs, inventory and the like. Increase efficiency and reduce the costs you can control.

By 2005, most progressive supply chains realized that better customer service could increase sales. Amazon forced supply chains across the globe to deliver goods faster and make it easier for consumers to order. Value-added activity, from gift wrapping to monograms on apparel to customized coffee mugs, increased supply chain effectiveness – the second E. Multiple corporations increased supply chain visibility so they could collaborate on everything from sales plans to volume increases to shortages of parts, materials and goods. Organizations that have visibility into their partners’ operations can adjust more easily.

Efficiency and effectiveness increased revenue and lasted until 2020. Broken by a global pandemic, the C-suite finally started paying attention to supply chain as a key operational concept, not just a cost center. Supply chain pros got respect, the first R in EERR.

Companies moved these supply chain pros into the C-suite. In return, the C-suite wants supply chain resiliency, the second R in EERR, completing the EERR cycle.

Resiliency would be much easier in a world without the aforementioned VUCA. Unfortunately, that is not the world we live in post-2020. I started tracking volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity in 2018, saw it increasing across global supply chains in 2019, and then explode when, as I wrote in my latest book Insightful Leadership: Surfing the Waves to Organizational Excellence,[8] “COVID-19 mated with VUCA, engulfing the old ways of doing business, washing them into the depths.”

Disruption, as I wrote, has become the new normal, not an occasional glitch. Even now, years after the height of the pandemic, people are still talking about a return to the new normal. However, beyond the pandemic, chaos wrought by digital and technological innovations that include robotics, data science and artificial intelligence, changes in the global economy and commerce in general, and geopolitical upheaval continue to wreck any semblance of settling into any new normal.

Witness the fury and frenzy of business and investment activity surrounding the November 2022 release of ChatGPT-3, a large language learning module. ChatGPT-3, its successor ChatGPT-4 and competitive generative AI tools like Bard, Bing AI and dozens more have affected numerous industries – something few, if any, businesses were planning for in October 2022. Companies are leveraging generative AI[9] for customer service, education, content creation, drafting emails, writing code, clinical decision support, medical recordkeeping and more.

As you can see, generative AI swept away that September 2022 “new normal.” The same thing will happen again. The future will depart from the past, not continue it. You need insights about the future, not data from the past. You must deploy those insights and discover innovations that will replace obsolete paradigms – and then do it all over again.

Let’s go back to cost savings – the first E in EERR. For years, companies aimed to buy raw materials, parts and products from countries with the lowest labor cost. That evolved into lowest manufacturing cost, then total landed cost (the total logistics costs of moving freight from point of manufacture to final destination, the point where your enterprise can start generating revenue) and then total delivered cost (how much it costs a company to deliver product to the customer, including manufacturing, marketing, sales, distribution, general and administrative expenses, etc.).

Longer lead times, of course, require more inventory. To avoid those costs, finely honed supply chains deployed just-in-time manufacturing and distribution systems, where raw materials, parts and goods arrived when needed instead of being stored “just in case” they were needed.

That worked well until the disruption of COVID-19, which required businesses to include the cost of lost sales. Furious executives have mandated that their new chief supply chain officers look for nearshoring and friendshoring options to reduce lead times. Shorter lead times and quicker inventory turns should allow sales to continue despite less inventory, adding optionality and increasing resiliency.

Of course, during this evolution, businesses have realized that the low-cost country has changed. According to the 2023 Agility Emerging Market Logistics Index,[10] labor in Mexico costs $3.90 an hour vs. $5.58 an hour in China. Rates are similar throughout Latin America.

Yet more than cost goes into the equation. More expensive skilled labor can produce more per hour than less expensive unskilled labor. (And I will discuss workforce issues later.) Still, for manufacturing that produces products for the Americas, lower-cost options are now in the same hemisphere, not half a world away in China.

That does not mean every obstacle has been cleared. Many companies have been reluctant to nearshore because raw material, component and supply chain sources still start in China and Asia. That’s why redesigning your supply chains means more than just moving final assembly to another country – it involves your entire ecosystem, starting with using the rest of the world as your depot for natural resources.

Supply chain risk, or the lack of resiliency, is another factor to consider when redesigning your supply chains for optionality. Sole sourcing, as the world has discovered, makes for brittle supply chains. Who knows when a large nation will invade a key supplier of grain?[11] (See Russia vs. Ukraine, 2022.) Who knows when China will restrict exports of key semiconductor materials like gallium and germanium? (Oh wait, that just happened.)[12] Heaven forbid if China invaded Taiwan, the world’s largest supplier of advanced semiconductors.[13]

These risks include transportation and port capabilities, the potential for weather disruptions and natural disasters, strikes or blockades (many think China would blockade Taiwan[14] instead of invading), corruption and crime. Even rare events add risks. Hawaii’s already devastating wildfires were made even more deadly by winds from Hurricane Dora, 500 miles away.[15] And a tropical storm just struck the coast of Southern California for the first time in 84 years.[16]

Beyond the fact that Mexico, the Dominican Republic and Latin America now compete well with China in labor costs, nearshoring to that area makes sense from a culture and language perspective. Although culturally distinct, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Latin America and the United States operate on similar time zones, and heavy immigration throughout the hemisphere at least adds to the cultural knowledge of leaders and their workforces.

The Container Revolution and Supply Chain Hubs

In 1937, Malcom McLean watched for hours as workers loaded cotton bales from his truck to a ship[17] at a port in North Carolina – essentially moving one box from one spot to another hand by hand.

He thought there had to be a better way. Nearly two decades later, on April 26, 1956, McLean launched a converted World War II tanker from Newark, N.J., to Houston. The Ideal X carried 58 of McLean’s newfangled metal containers and 15,000 tons of petroleum.[18]

Thus was born intermodal container shipping. Quickly transferring McLean’s stackable boxes dramatically dropped expense and time. Loading that used to cost an estimated $5.83 per ton now cost an estimated 15.7 cents per ton.[19] According to maritime container expert John D. McCown Jr.’s book Giants of the Sea, “In less than eight hours of cargo activity, the new process had loaded the same amount of cargo that it would have taken some three days to load with the traditional breakbulk loading process.”[20] The security of locking thousands of goods, parts and products in boxes also decreased theft.

The ramifications of McLean’s breakthrough have been enormous. The Port of New York[21] decided to develop a new container port in Elizabeth, N.J. Ports worldwide followed suit, and businesses sprang up to develop, manufacture and sell the material handling equipment to transfer containers back and forth from truck to ship to railroad car. The United States alone has 2,270 terminals that handle some form of intermodal transfer. While most serve specific local traffic, about 20% move significant volume.[22]

Massive container ships can carry up to 24,000 TEUs (20-foot-equivalent units.)

The growth in container ship size forced the Panama Canal to add a widened channel that opened in 2016. The $5.25 billion project doubled the canal’s capacity and added a shipping lane that was 70 feet wider and 18 feet deeper than the original locks. The original canal can handle Panamax-size ships that carry up to 5,000 TEUs. Neopanamax ships that carry up to 14,000 TEUs must go through the wider lane. Panama’s authorities say 96% of container ships afloat can traverse the canal.[25]

Canal improvements, however, failed to solve every disruption in East-West shipping. While only 4% of container ships cannot fit through the widened channels, canal operations rely on fresh water. A recent severe drought has forced the Panama Canal to limit both the number and draft of ships traversing the canal each day.[26] Canal authorities are working on short- and long-term solutions that should minimize such disruptions in the future.

Still, international shipping has become the backbone of the world economy. About 80 percent of goods are carried by sea, and volume has grown from 0.1 billion metric tons in 1980 to 1.95 billion metric tons[27] in 2021.

Large ports now populate the coastlines of every continent, and shipping hubs have become economic transformers in their own right. The Port of Singapore, the second largest in the world, handled 37.49 million TEUs[28] in 2021. Before the explosive growth of global shipping, Singapore, which repeatedly ranks as the world’s “top maritime city,”[29] had a per capita GDP of only $500.[30]

Port Automation

Want to discover more about port automation systems with Tompkins Ventures? Contact us.

After decades of evolution, Singapore’s GDP per capita reached $82,794[31] in 2022. During the intervening years, Singapore, now the supply chain hub of the East, developed clear strategies and detailed long-term plans concerning every aspect of logistics. Within Singapore, the country transformed roads, buses, mass transit, parking, taxis, restricted travel areas, fare collections, vehicle ownership, air travel and freight, cycling and every aspect of mobility. The port’s master planning between 1965 and 1972 focused heavily on basics: increasing labor productivity and fork truck and crane utilization.

In the early 1970s, port authorities turned their focus toward information technology (IT) and containerization. IT followed an evolutionary process, starting with accounting, port analytics, communications, operating systems, then EDI, bar code readers and simulation, with Artificial Intelligence added in 2021. Containerization’s path started with gantry cranes, then mechanized gantry cranes and automated guided vehicles. Areas targeted over the last 10 years have included enhancing customer services, employee training and development and a strong focus on sustainability.

Singapore’s growth provides a template of successes and mistakes that other potential logistics hubs can learn from. For the Eastern Hemisphere, Singapore is a crossroads for global trade. The Dominican Republic could see similar success as a logistics hub for the Americas and the Western Hemisphere.

The Dominican Republic could benefit from the gradual move away from China, which over the past three decades has become the factory of the world. Political authorities and business leaders in the West, concerned about relying on the Chinese Communist Party and a potential invasion or blockade of Taiwan (more on China below), have been pushing to decouple supply chains from the world’s second-largest economy.

Despite dire headlines predicting China’s imminent collapse, the East Asian giant will remain a major player in global trade. After all, decoupling supply chains from China is no easy or overnight task. Remember, it took decades to build those supply chains from scratch. Moving final assembly is only step one. Sure, maybe Vietnam now makes your mobile phones, and the Gorilla Glass comes from Taiwan, but Vietnam likely sources the circuit board, antenna, battery, microphone, speaker, case and other parts from China. The $20 million you thought you removed from China might total only $2-$3 million.

A complete end-to-end supply chain involves everything that goes into the goods you provide. If raw materials and parts still come from China, your supply chains still rely on a single, risky source.

And many fear that the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada have become so dependent on China for a number of exports that we may have reached the point of no return. Categories of concern include consumer goods, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, consumer electronics, energy – especially green energy inputs like lithium – information technology, food and agricultural inputs, infrastructure inputs and more.[32]

Take Australian mining giant Rio Tinto. That enterprise’s chief executive officer has said the West needs to match China when it comes to resources like minerals and materials. But the company’s largest shareholder is Chinese state-owned aluminum producer Chinalco.[33]

The Dominican Republic – The Hub of the West

Total deglobalization – every country producing every good and service its population needs – is not achievable or desirable. Destroying the benefits of economies of scale and comparative advantage certainly will destroy the world’s economy. But the move toward relying on countries that, if not allies, are at least more friendly, is a tough but necessary task. It also offers opportunity to heretofore left-out countries.

About 800 miles southeast of Miami lies the Dominican Republic. The country has several ports, available land for expansion, free trade agreements with the United States (DR-CAFTA) and Europe and sits astride major East-West and North-South trade routes to the Americas. The country has the ideal location and public-private leadership to capitalize on shifting, yet growing, global trade.

For calendar year 2022, the five busiest U.S. East and Gulf Coast ports (New York, Savannah, Houston, Norfolk, Charleston) imported 12,720,972 TEUs, exporting another 5,674,053 TEUs. Smaller East and Gulf Coast ports generally handle an additional 25-30% of those numbers. While West Coast ports that have lost market share plan to go after every pound of freight they can, executives admit that some of that lost trade won’t return. I think the broader supply chain shifts will continue to increase the share of imports moving through East Coast and Gulf Coast ports.[34]

More than half (58%) of the U.S. population lives east of the Mississippi River.[35] The Dominican Republic’s geographical location is perfect for transshipment and eCommerce fulfillment for the eastern U.S. In fact, I believe the Dominican Republic could support two-day shipping to 60-70% of the U.S. population, capturing much of that market and much of its continued double-digit growth.

The Dominican Republic can benefit from the significant progress Singapore and other modern ports have made, as much of the digital transformation and IT work is now available as standardized software.

The Caribbean country’s location also provides that country’s leadership a great opportunity to capitalize as supply chains seek new sources of raw materials, goods and parts. The Dominican Republic could become the Singapore of the West, a major supply chain hub rivaling any on the globe. Any decoupling from China will lead to new supply chain flows across major corridors:

East-West

- From Asia and west coasts of North and South America through the Panama Canal to the Dominican Republic and then onto the east coasts of North and South America

- From Africa and Europe to the Dominican Republic to the east coasts of North and South America and through the Panama Canal to the west coasts of North and South America and Asia

South-North

- From South America to the Dominican Republic to North America

- From North America to the Dominican Republic to South America

The decades-long evolution of supply chains has led to impressive economic growth that has yielded more prosperous lives for billions of people. But single-, lowest-cost sourcing has left those supply chains brittle, a dangerous state for a world of perpetual disruption. Essentially, global disruptions are forcing your organization to simultaneously pursue deglobalization (less integration with previous major partners like China) and globalization (more interdependence with economies, cultures and populations outside of China). Rerouting trade, creating new logistics hubs and involving more areas of the world than ever before – optionality – will make your supply chains, countries and businesses more resilient.

The Necessity of Technology

Today, many companies’ supply chain operations resemble the dark ages. They rely on antiquated systems and spreadsheet masters. They use labor to pull data where systems could accomplish the work in less time and at less cost.

Today’s Transportation Management Systems (TMS) technology and digital supply networks use advanced software, technical expertise, artificial intelligence, machine learning and cloud computing to transform your current, non-resilient supply chains. In fact, fully enabled digital supply networks are the only way to achieve resiliency – that second R in EERR.

The right TMS optimizes transportation cost and mode, giving you the visibility to deliver on time, every time. Your enterprise can improve service levels while distilling data into understandable interfaces that support decision-making at the rapid pace demanded by today’s market. Choose the right transportation mode and carrier while automating intelligent parcel routing decisions within eCommerce shopping carts for optimized order entry, packing and shipping execution processes.

Beyond your typical first or second options that provide best service and rates, the right TMS increases your logistics optionality. When capacity is tight, your TMS can provide choices that allow you to go eight or nine carriers deep.

TMS and Your Digital Supply Network

Want to discover more about Transportation Management Systems and digital supply networks with Tompkins Ventures? Contact us.

The right TMS will cover every aspect of freight execution and management, including order planning, rate/carrier selection, shipment execution, track and trace, and match pay and freight bill payment.

Digital supply networks move that visibility beyond your enterprise, enabling a true end-to-end supply chain.

Keeping pace in today’s world means tracking all raw materials/components/

parts from their entrance into your end-to-end supply chain until their exit as finished goods – supply chain visibility at its best, from 19 suppliers upstream to 36 suppliers downstream. Enterprises in your network need a real-time single version of truth, where all suppliers, carriers, customers, manufacturers and distributors operate on one database and one user interface, promoting cooperation between enterprises and allowing real-time, simultaneous planning and execution. Decision-making requires an AI/machine learning/cloud computing-powered network that can autonomously and simultaneously plan and execute many decisions (adjust/create orders, modify inventory policies, forecast transport capacity, optimize transport) across multiple parties, not one enterprise. Only significant issues escalate to human supervisors for action.

A fully enabled digital supply network will:

- Handle high degrees of complexity,

- Eliminate latency with real-time information,

- Autonomously resolve many problems with artificial intelligence and machine learning,

- Optimize the entire chain, not just specific links,

- Harvest the benefits of internal and external synergies even while facing VUCA and

- Drastically reduce the cost of goods sold across the dozens, hundreds or thousands of entities that make up your supply chain.

Natural Resources – The World Is Your Supply Depot

Production may be the heart of creating value, but nobody produces anything without natural resources. Many are under the mistaken assumption that China has almost a stranglehold on the world’s natural resources. After all, virtually every global supply chain starts or meanders into that country.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact, the value of China’s natural resources ranks only sixth in the world, behind, in order, Russia, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Canada and Iran.[36] China relies heavily on other countries for iron ore[37] and refined copper.[38]

However, China is way ahead of many Western nations in securing access to raw materials. As noted above, a Chinese-state owned company is the largest shareholder in Australian mining giant Rio Tinto, and Australia exports virtually all of its lithium to China.[40] China dominates the rare earth minerals (36.7% of rare earth reserves) necessary for the wind turbines, solar panels and batteries the world must produce to transition to green energy.[41] And, as also noted above, China just restricted exports of gallium and germanium, key semiconductor materials.

China produces 98% of the world’s gallium, and the U.S. has no national stockpile. Moreover, “Gallium nitride (GaN) is foundational to nearly all the cutting-edge defense technology that we produce,” according to the head of advanced military projects at Raytheon.[42]

That leaves the rest of the world playing catch up. Russia’s conflict with Ukraine has upended oil and natural gas exports to Europe, and the EU is paying attention. Recently, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen signed a memorandum of understanding to develop value-added lithium projects in Chile, hopefully securing sources of green energy.[43]

Such new resources outside of China are vital. A volcanic lakebed in the Western U.S. could hold the largest lithium deposits in the world. The United States has only one operational lithium mine. Another is being held up in litigation.[44] Yet another lithium project is being developed under the Salton Sea in California.[45]

After all, the world is more than China, and if you can locate raw materials in geographic regions close to your production facilities, you reduce the time and cost of transportation.

In my mind, that’s why India has the best chance of replacing China as, if not THE factory of the world, a major factory of the world. India is the globe’s most populous country, so the country can be a market unto itself. The country’s mineral resources include high-quality iron ore, ferroalloys (notably manganese and chromite), copper, bauxite, aluminum, zinc, lead, gold, silver, limestone, dolomite, rock phosphate, ceramic clays, mica, gypsum, fluorspar, magnesite, graphite and diamonds.[46]

Already, major tech firms like Apple, Samsung and Dell are planning or considering plans to add manufacturing on the subcontinent.

Apple has increased iPhone production in India to nearly 7% of its output. That includes the latest iPhone 15.[47] Samsung has been steadily increasing smartphone production in India[48] and is considering the country for a 5G equipment production hub.[49] Dell is one of 40 companies, including Hewlett Packard, Foxconn, Lenovo, Acer and ASUS, looking to take advantage of manufacturing incentives to build plants in India.[50]

All this growth will require additional infrastructure and services: more transportation, logistics/supply chain and warehousing/distribution centers/fulfillment centers. Tompkins Ventures and our Indian partners are already working to find, build and service the necessary infrastructure. Major companies like Blackstone are expanding their Indian warehouse portfolio,[51] and DP World is developing a $510 million mega-container terminal in India.[52]

But there are still a lot of headwinds, like low labor productivity, insufficient physical infrastructure and potentially slow decision-making because of too many stakeholders.[53] India has the world’s fourth-largest reserves of coal – a notoriously polluting energy source – and does not produce enough petroleum and natural gas to serve its population.[54]

Elsewhere in Asia, ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries have abundant natural resources. Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei have considerable reserves of oil and natural gas. Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia account for more than half of the world’s production of tin.[55] Tompkins Ventures research has found many ASEAN countries ideal for manufacturing electrical components (The Philippines), semiconductors (Thailand) and more. The top 5 countries (Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam) are already industrialized. Workforces have the required skillsets at a significantly lower labor cost – warehouse operating labor in Indonesia can run $119 a month, very favorable compared to $600,000 robots. Data centers are another ideal option. And Indonesia has moved to restrict exports of raw materials, especially nickel, to encourage development of automotive battery production.

Middle classes in these countries are growing, making them potential markets, not just production centers. And the region’s population tops both the U.S. and the EU – and skews younger.

All these factors minimize risk, and investments are coming from Japan, China, Saudi Arabia and South Korea – semiconductor plants, logistics capabilities and more. Governments are responding with even more infrastructure improvements.

Closer to the U.S., Canada, Central and South America have their own advantages.

As noted above, Canada has abundant natural resources, including potash, petroleum, coal and iron ore.[56] Canada also has solid manufacturing capabilities and a healthy labor supply at a relatively competitive cost.[57] Canada has particularly strong relations with the United States. Border crossings, from the viewpoint of both tourists and logistics professionals, are seamless, despite sharing the longest land border in the world. Along with Mexico and China, Canada is one of the United States’ top three trading partners, and the countries cooperate on a long list of mutual interests – defense, trade and the desire to strengthen, not weaken, the relationship.[58]

In networking with Brazilian manufacturers, I have discovered that the largest country in Latin America has robust manufacturing capacity for shoes, furniture and other goods – and access to plenty of raw materials to fuel that manufacturing base. But although Brazil is the sixth-largest furniture producer in the world, producing 430 million pieces a year, the sector’s current capacity utilization is only 69%.

Global Connections

Contact Tompkins Ventures to discover more about opportunities in India, the ASEAN countries, the Caribbean and Central and South America.

That leaves huge potential for nearshoring at all quality levels (from medium-density particleboard (MDP) to solid wood, standard and premium finishing).

For garment production, Latin America and the Caribbean encompass the sector’s full supply chain – raw materials, spinning, weaving, processing and manufacturing, with Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico and Peru being important centers of production. Despite those capabilities, Latin American and Caribbean countries only account for 1.4% of global textile exports. Of that total, Brazil exports the most at 57%, with Peru (14%) and Colombia (almost 10%) a distant second and third.[59]

South America has about one-fifth of the world’s iron ore reserves and more than one-fourth of the world’s copper reserves, along with large amounts of tin, zinc, lead, oil and natural gas.[60]

Moreover, beyond sourcing manufacturing close to the raw materials, freight costs from South to North America are dramatically cheaper than freight costs from Asia – in fact, the cost of shipping from Brazil to the U.S. is half the cost of shipping from Asia.

Another continent, Africa, also could benefit from a greater synthesis within the global manufacturing and supply chain ecosystem.

Africa has abundant natural resources: arable land, 30% of the world’s mineral reserves, 8% of the world’s natural gas, 12% of the world’s oil reserves, 40% of the world’s gold, 90% of the world’s chromium and platinum, and plenty of cobalt, diamonds and uranium, according to the U.N. Environment Programme.[61]

Tanzania, in particular, has huge deposits of high-quality, low sulfur coal.[62] West Africa produces enough high-quality cotton to fuel a textiles boom, according to the nonprofit Tony Blair Institute, and can offer vertical integration along the supply chain. West African nations export 90% of their cotton unprocessed, leaving plenty of raw materials to fuel a manufacturing boom.[63]

And just like Central and South America, Africa is closer to the Americas – and a lot closer to Europe. West Africa can ship to Antwerp in nine to 13 days, New York in 14 to 22 days. Shipping from China to Antwerp can take 26 to 40 days.[64] The same ship from China to New York? Try anywhere from 32 to 49 days.[65]

Lower transit times between the Southern and Northern Hemispheres of the Americas and Africa and the Americas will help companies save on shipping fuel, reducing carbon dioxide emissions and enhancing the sustainability of these nearshoring options.

Of course, the lowest transit time would be producing in your backyard. But many people think moving manufacturing back to the United States – reshoring – does not happen without help from taxpayers. And recent tax credits for making batteries, solar-power equipment, semiconductors and other technologies support that notion. The credits are drawing more investment in U.S. factories, with the EU following suit.[66]

However, as noted above, the value of natural resources in the United States ranks No. 2 in the world, behind first-place Russia but well ahead of sixth-place China.[67] And, according to a Reuters-Maersk white paper, supply chain disruptions have changed client sourcing strategies for 77% of logistics and technology service providers, and 37% of manufacturers plan to change manufacturing locations in the future.[68]

Guess what? Some of those companies have successfully returned manufacturing back to the United States. Bath & Body Works, for example, spent years reshoring not just production, but almost its entire supply chain, from China to the United States. One pump that required $2 million in capital investment and employed 50 people in China is now manufactured in Ohio by 10 people at a capital investment of $12 million. But such proximity means those pumps arrive in less than a month, not the previous five months.[69]

Proximity can slash lead times, which can slash costs. Some companies who have gone through such reshoring initiatives have reduced lead times by more than 80% and product costs by 20-40%. How? By quick response manufacturing, pioneered by the Center for Quick Response Manufacturing at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Their contention is that actual direct labor costs – machining, fabrication, assembly – account for less than 10% of many companies’ annual operating costs. Half of a company’s annual budget pays for overhead, selling and administrative costs, with the remaining 40% going to purchase raw materials and components.[70]

Long lead times (think of the five-month pump for Bath & Body Works) drastically increase those indirect costs like forecasting, planning, warehousing, expedited freight costs in case of stockouts, and time for sales and administrative staff to manage the processes and the delays.[71]

Say your company’s operating costs are $100 million. By concentrating on direct labor and offshoring to a low-cost country, maybe you save 90% of 10% of your costs – $9 million. However, if instead you can save 20% on 50% of your overall costs, savings to your bottom-line total $10 million.

Circularity

Moving your operations toward the circular economy – reusing, repairing, remanufacturing and recycling products and materials – offers another reshoring option. Every day, your business throws away untold things that can be reused. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the current largely linear economy throws products away at their end of life. The circular economy reuses, repairs, remanufactures and recycles products and materials, keeping them in circulation far longer.

Lexmark and Xerox (printing and imaging products), Fernish (furniture and décor), Returnity (packaging), HILOS (shoes),[72] Caterpillar (heavy machinery) and GE Healthcare (imaging equipment)[73] are just a few companies that design products with reuse and remanufacturing in mind.

Transitioning to a circular economy requires creative teams and innovation. Reusable packaging, for example, could be a tough sell if you expect consumers to return the material. However, the concept has proven viable in internal logistics between distribution centers and stores. And a full 74% of supply chain leaders expect to increase profits in the next two years by applying circular economy principles.[74]

Of course, you will have to re-engineer your sourcing supply chains and procedures. You need new locations for repairing, remanufacturing and managing waste. Your procurement processes can even look for outside sources of circular materials. Your partners, especially suppliers and distributors, also play a role.

Companies that are succeeding in this arena increase their sustainability, improve profitability and benefit from shorter and compact supply chains while simultaneously combatting global warming. Manufacturing or remanufacturing at least some of your products in the United States and Europe have added benefits. Many countries with low-cost labor, like China and India, generate much of their energy from coal, which emits massive amounts of carbon dioxide.

Coal accounts for only 11% of U.S. energy consumption. Petroleum and natural gas – cleaner than coal but not really clean – account for much of the rest, with emission-free nuclear and renewable energy sources contributing a total of 20%.[75]

Latin America and the Caribbean have had even more success, generating 63% of the region’s electricity needs from clean sources in 2022. Hydropower is the No. 1 source (think of the vastness of the Amazon River) at 45%. Wind and solar are a distant second at 11%. The region has avoided the coal dependency of many developing regions, as coal provided just a paltry 4% of the area’s electricity needs.[77]

Data from Visualcapitalist.com

By contrast, other regions fare much worse in green energy sources.

Coal produced nearly 75% of India’s voracious and growing energy needs in 2022. The country is the third biggest fossil fuel polluter, behind China and the United States. Although, to be fair, the nation installed 13.9 gigawatts of new solar capacity, a 28% increase.[78] While wind and solar generation are growing in Africa, fossil fuels still dominate domestic energy supply at 71%, and the continent also relies heavily on coal.[79]

Clearly, the world is struggling with the transition to green energy sources – some regions more than others. And in a world where consumers care about ESG (environmental, social and governance) issues, enterprises need to pay attention to where their natural resources come from, the environmental costs of acquiring them and more efficient ways to use them to increase sustainability.

The point is not that all production and raw material sourcing should come from, say, Latin America because of its head start in emissions-free energy, or that countries should never source from India, or should build everything in the United States, Europe, Africa or any SINGLE location.

In the end, your future supply chains (notice the plural there) could source some manufacturing in Africa; send some raw materials from Africa to manufacturers in South America; include operations in the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia; and source raw materials and manufacturing in the United States, Canada and Europe.

Remember, raw materials are the basis of all products. Global supply chains are not just about final assembly – they reach all the way back to the raw materials we mine, grow and hunt for.

In sourcing raw materials, keep in mind that your source likely sells to your competitors. That could hinder availability if demand increases and multiple enterprises bid from the same source. Maintaining good relations and contracts with important suppliers could position your enterprise as your suppliers’ “first choice.”

Beyond that, optionality is once again the key. And that means a strategic decision to, if possible, secure duplicate suppliers. Yes, that carries additional risks and costs. Administrative costs will be higher. You might lose leverage by not having one “preferred” supplier. Your chances of dealing with a sketchy supplier (environmental issues, poor labor conditions) increase. But you also have more options to drop such suppliers.

This nearshoring/friendshoring is truly challenging. You must redesign your supply chain all the way back to the raw materials. This could take years and could be expensive because your current suppliers have spent decades establishing hubs or clusters to process your raw materials. Rebuilding your entire ecosystem will require a lot of work, access to the right labor, the development of an entirely new support structure and the ability to navigate shifting political realities.

Government, Global Supply Chains and Globalization

Governments, both local and national, can have a major voice on globalization through policy choices.

Policies on trade, the environment, labor and product specifications all have their impact.

Tariffs and taxes restrict trade by increasing the costs of imports, while subsidies lower the cost of domestic products. While such policies might make domestic production cost competitive, the distortions reverberate throughout a product’s supply chain. Steel tariffs under both the George W. Bush[80] and Donald Trump administrations[81] cost more jobs than they saved by making steel more expensive for downstream U.S. manufacturers.

Governments can also weaponize trade through restrictions and resource nationalism. China has long slapped trade sanctions on companies and countries that displease them and has curbed exports of key materials. Recently, the United States placed export controls on cutting-edge semiconductors for artificial intelligence systems. The idea is to undercut China’s increasing military capabilities.[82]

Environmental policies like clean air and water regulations increase production costs, affecting trade. But they also can protect consumers and the environment, as well as driving innovation and creating markets for environmentally friendly technologies.

Likewise, policies restricting or taxing carbon dioxide emissions can affect the cost of goods from high-emission industries. On the other hand, they could spark innovation in low-carbon technologies, services and renewable energy technologies.

Subsidies and land-use restrictions affect the competitiveness of agricultural products, along with food security and rural development. Rules on mining and drilling affect the ability to extract, use and export minerals and fossil fuels. Remember, the United States has only one working lithium mine.

Product disposal is another environmental issue. Recycling and circular economy policies can create demand for recyclable materials and reduce the demand for virgin materials, making mining and forestry restrictions less of a problem. Take product responsibility laws, for example, which require manufacturers to manage the lifecycle of their products. To comply, your teams must plan for disposal once your products reach their end-of-life.

Increased costs – sure. But, once again, such policies can stimulate innovation, creativity and new markets.

Labor policies significantly impact trade. In the United States, OSHA regulations aim to ensure safe and healthy working conditions. Production costs could increase – unless you realize that unhealthy workers suffering from musculoskeletal disorders aren’t really that productive. Even less so if they are disabled from work accidents.

Policies on wages, overtime, benefits, health insurance and retirement contributions also increase labor costs. Of course, such policies also attract employees in a competitive workforce situation.

Product specifications in pharmaceuticals, food, cosmetics and consumer products also increase costs but aim to protect safety.

In pharmaceuticals, stringent specifications regarding efficacy, safety and quality make it challenging to bring products to markets. The cost of bringing a drug to market in the United States averages $1.335 million, according to a 2020 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association.[83] However, they also ensure high standards, protecting public health. Many of these regulations trace back to the thalidomide scandal of the 1960s that resulted in thousands of severe birth defects.[84]

Food specifications, including hygiene standards and ingredient restrictions, exclude products that don’t comply but protect consumers from potential health risks.

In the cosmetics industry, regulations concerning ingredients, labeling and safety testing can restrict trade by increasing production costs and limiting market access. However, they also safeguard consumer health and safety.

Finally, consumer product specifications, such as safety standards and labeling requirements, impose additional costs on manufacturers – and therefore, the end customer. But their purpose is to ensure that products are safe, enhancing consumer confidence and potentially stimulating demand.

Who Will Do All This Work?

No matter where you source or manufacture and how you re-engineer your supply chains, your enterprise needs to consider workforce availability, productivity and size. Factors include a country’s knowledge and expertise regarding automation and robotics; the cost and training necessary; and the ethics and morality of how countries treat their workers.

Regardless of how inexpensive a country’s workforce is, you do not want your products and supply chain associated with forced labor, inhumane working conditions, human rights violations, child labor and the like.

Here are some key considerations:

- Define your workforce needs and criteria. What skills, qualifications and experience does your organization need? What are your expectations for productivity, quality and cost? Measure and compare these factors across countries.

- Use reliable sources of workforce and labor market information. The data sources below can help you understand workforce size, composition, skills and trends among different countries:

- The Best Countries rankings by U.S. News & World Report, which includes a subranking of countries by their skilled labor force based on global survey respondents.

- The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has a keyword searchable data explorer (available at https://data-explorer.oecd.org/) that allows you to download comparative country information based on numerous factors important in workforce consideration.

- The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs 2023 report brings together perspectives from 803 companies that employ more than 11.3 million workers across 27 industry clusters and 45 economies from every region of the world.

- Compare and contrast workforce characteristics and performance across countries. Using the data and analysis from the sources above, you can examine different countries based on:

- Labor force size and growth.

- Workforce educational attainment and skill level.

- Wage level and labor cost.

- Workforce productivity.

- Labor market regulation and flexibility.

- Workforce diversity, equity and inclusion.

- Labor skills set and training by industry.

- Workforce turnover rate.

- Availability of labor training centers.

- Availability of workforce development centers.

Workforce metrics can help you predict risks and shape strategies for where and when you move your operations. This includes whether you simply expand your organization’s sourcing and manufacturing capabilities into another country (or countries), reshore all or some of it back to your home country, or simply add additional capabilities in other regions to handle growth. And you likely will use a combination of the above – optionality.

Deloitte Insights has a great framework on developing ways to measure and monitor workforce readiness to meet new demands. Although Deloitte concentrated on producing data from internal systems, their queries and concerns are spot on today. They certainly apply when examining workforce capabilities in other nations, regions and continents. Beyond the basics like headcount, salary, turnover, workforce composition, diversity and the like, enterprises need to know a prospective workforce’s talent mobility, your brand’s status, the ability of workers to reskill and whether leadership potential exists.[85]

Talent mobility, for example, can cut both ways. Will talent in the country or region you are targeting for new or expanded operations be able to relocate where you plan to expand? If they can relocate so easily, how will they respond to other opportunities, which could come from your competitors?

That plays into your brand reputation. Your company may be perceived differently in different jurisdictions. Perhaps you have a great reputation for worker well-being, community engagement and environmental considerations in country A, but a reputation for overwork, exploitation, worker mistreatment, environmental mismanagement or worse in country B. Country A would likely be a better choice.

Looking for New Markets?

Contact Tompkins Ventures to discover more about expanding your enterprise’s opportunities in new countries and continents.

Organizations can combat poor reputations by self-reporting workplace well-being – after improving the metrics, of course. Another Deloitte Insights report made the case that publicly reporting such metrics is in your company’s best interests. More than half of that survey’s respondents would 1) trust their company more if it publicly reported workforce well-being metrics, and 2) take a job with another company that publicly reported workforce well-being metrics.[86]

Other factors can affect your sourcing decision, including your prospective country’s political stability and security; trade policies and agreements with your home country; infrastructure and logistics; cultural fit and communication with workers; and the environmental and social impact of your sourcing.

The three sources mentioned above are great places to start. First, of course, is the U.S. News & World Report subranking of countries by skilled labor force, part of that magazine’s Best Countries rankings. For a deep dive, you can spend hours or days browsing the OECD’s keyword searchable data explorer. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs 2023 report is another massive repository of information.

The skilled labor aspect is crucial. After all, workers who earn $10 an hour while producing 100 units are more productive than others who earn $1 an hour while producing five units.

OECD data includes average annual hours workers work, average annual wages, collective bargaining coverage, gender wage gap, minimum wage, wage gap by age and more. Information on each country’s government includes stability, transparency, openness, disclosure of public information and more. Other data includes venture capital investments and population data and projections. Environmental considerations include air and climate and environmental policy. Innovation and Technology includes broadband access, entrepreneurship, industry, information and communication technology and research and development (R&D).[87]

The World Economic Forum’s report includes the global labor market landscape, how macrotrends and technology adoption are affecting industry transformation and employment, how those changes are disrupting current skills and forcing workers to upskill, and strategies on finding, developing and keeping talent.[88]

News sources and nonprofits active in-country can be other resources. The Tony Blair Institute, mentioned above in relation to sourcing cotton and textiles in West Africa, notes that the region includes a young population that offers “trainable and accessible labor” and favorable policies.[89]

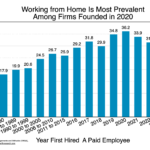

Whatever country, or countries, your organization enters, you will have to understand that workplaces have changed across the globe. Much of the news in the United States and Europe involves the fight between white-collar workers who want to keep their remote-hybrid status and bosses who want their charges back in the office under their thumb. But companies worldwide have embraced remote and hybrid work to varying degrees. A Cisco study found that employees in India believed 63.1% of their employers supported hybrid work, with 59.6% in the Philippines and 55.1% in South Africa. Spain (21.6%), Poland (20.1%) and Korea (18.9%) were less receptive to hybrid work. And in 2021, employees in general worked more days from home in emerging markets than in developed markets.[90]

Many work-from-home and remote work studies concentrate on white-collar workers. But the ability to manage family business, take care of sick children or simply handle life should extend to the blue-collar set – and much of what your enterprise will be sourcing in new countries involves production of materials or products, which requires in-person work.

What Steven M.R. Covey calls “trust and inspire” leadership (based on his book Trust & Inspire) must replace command-and-control leadership. All of the issues involved in recruiting, motivating and retaining a solid workforce – medical care, family leave, childcare and childhood support, flexible scheduling, employee assistance programs – can really be divided into my three-bucket approach to reinventing work:

- Insuring adequate health and medical benefits for your workforce.

- Devising policies for family continuity and employee support.

- Providing optionality for your entire employee base – not just the laptop class.[91]

For bucket No. 1, turn to your HR department. Buckets No. 2 and 3 are more complicated but doable.

For bucket No. 2, organizations ranging from UNICEF to regional nonprofits have sample policies, advice, even certification programs.[92] New Mexico, Wisconsin and Australia have such programs. Perhaps your region does as well. Your HR department can select what makes sense for your enterprise.

For bucket No. 3, job-sharing – cross-training multiple workers for multiple roles – can help to a point. But there’s always the risk of too many employees needing time off at the same time, not to mention issues with peak seasons.

That means you’re going to have to develop a flexible workforce, particularly for activities that must happen at the worksite – i.e., blue-collar work. If your operations need 100 full-time employees, a possible solution involves pairing 90 full-time employees with 20 flex workers. You can develop such part-time workforces on your own, run the gamble of using temp agencies or work through specialty flexible labor platforms. (Task4Pros in the United States and its Brazilian subsidiary, MeuChapa, are examples.)

You can mitigate such risks by carefully evaluating the labor skills and capabilities of your potential suppliers before making a decision. Once in-country, your organization should invest in training and developing your workforce, monitor their performance and quality and establish clear communication and feedback channels. And yes, even if they are in another country, they are YOUR workforce.

A Level Playing Field? Hardly

“Every individual … neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it … he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.”

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

At its best, globalization provides a level playing field. But as we know, when politics enters the fray, a level playing field can be an insurmountable expectation.

In general, people and companies act individually, looking out for the best interests of themselves, their families, their shareholders and their bottom line. Pursuing your own interests in the context of global supply chains enables commerce and income growth. Individuals and entities specialize, establish economies of scale, profits grow, and more people and enterprises can purchase more goods and services from people and enterprises who specialize in other fields.

Like I mentioned in the Executive Summary, that village goes global. Thus, global supply chains are the heartbeat of improving global living standards.

Until the 1970s, China’s Communist Party held command and control over that country’s centrally planned economy. Diplomatic thaws that started with U.S. President Richard Nixon’s historic 1972 visit to China[93] culminated in renewing diplomatic relationships in 1979 under U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Chinese Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping.[94]

By 1980, China significantly reduced tariffs and undertook industrial reforms. By 1984, the U.S. had become China’s third-largest trading partner and China had become the United States’ 14th largest trading partner. When China became the 143rd member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, Western leaders hoped open markets and free trade would allow access to the large and growing Chinese market, elevate China to the club of global trade, increase prosperity for all and spread democratic values throughout China.[95]

Some of this happened. China’s integration into global markets has lifted nearly 800 million people out of poverty in the last 40 years.[96] Many Western companies profit from access to the Chinese market, as many Western consumers benefit from low-cost goods.

However, while China’s economy and market power skyrocketed after joining the WTO, the country’s leaders never embraced a level playing field nor adopted democratic values. Instead, China pursued what many called “state capitalism,” where even privately owned enterprises are subject to the whims of the Chinese Communist Party.[97]

The CCP thoroughly integrated China’s political and commercial agendas. They often heavily subsidized key competitive sectors, including aerospace equipment, biologics, electric vehicles, railway equipment, robotics, wind turbines and others. China and Hong Kong (which is China after the 4-year-long crackdown on pro-democracy forces),[98] account for more than half of the world’s intellectual property theft.[99]

China has become the world’s second-largest economy, the world’s largest exporter and has seen GDP grow from $310 billion in 1985 to $18,100 billion in 2022.[100] China has become the factory of the world. A large share of manufactured goods has some part, if not every part, of their supply chain originating in China.

Such growth and prosperity have helped China push forward its Belt and Road Initiative. This network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, port facilities, shipping lanes and other infrastructure has engaged 147 countries across the Asia Pacific region, Africa, Saudi Arabia, Latin America, Europe and Russia. This encompasses two-thirds of the world’s population and 40 percent of global GDP. China’s stated goal is to construct a large, unified market of international and domestic markets for regional cooperation, improved trade, mutual understanding, trust and innovative capital inflows, talent pools and technology databases.[101]

Notably, the only G7 member to sign on, Italy, now has qualms about the whole deal.[102]

Such concerns about China’s growth and power have accelerated in recent years, as the West has taken note of how China has used loans, tariffs, quotas, subsidies, tax incentives and free trade zones to establish an uneven playing field. Every action begats a reaction, and some Western nations have responded with their own loans, tariffs, quotas, subsidies and tax incentives, increasing the deglobalization theme of the post-Great Recession years. The West’s trade war response has exacerbated macroeconomic issues in China, and many are saying that country’s 40-year economic boom is over.[103]

Chinese households are reducing their willingness to spend amidst uncertainty, hampering the housing sector. Beijing’s zero-COVID policies and regulatory crackdowns have threatened the service sector, which shed 12 million jobs between 2020 and 2022.[104] Exports and imports have fallen.[105] Analysts say the Chinese government’s aversion to Western-style consumer-led growth will prevent changes from the current centralized control to market-oriented reforms.[106] Major shipping and logistics companies are acquiring facilities outside of China, especially Vietnam, India and Malaysia.[107]

Despite the drumbeat of bad headlines, reports of China’s demise are likely premature. Short of outright war, any Western decoupling will be slow and possibly painful. But much of the U.S.-led bloc of nations is moving in that direction.

China will remain a player on the world stage. Its population, economy, manufacturing base and integration into global supply chains spans the world. Through Chinese-owned COSCO Shipping, the country operates and manages 367 berths at 37 ports worldwide, according to the company website. COSCO’s reach includes Europe, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, South America and Africa. And it’s increasing its presence with expansions in Hamburg, Germany[108] and Peru.[109]

Friends and Enemies

In paragraph five of the “Globalization vs. Deglobalization” section, I mentioned how the retreat from globalization is dividing the world into various power blocs. Although countries like China have benefited greatly from globalization, the nation’s policies have really pushed toward deglobalization for the last 20 years. Western nations have joined that push for the last 10 years.

When Russia, which has had a “special relationship”[110] with China for years, invaded Ukraine, the U.S. and NATO supported Ukraine with arms and economic sanctions against Russia to isolate Vladimir Putin’s regime. Like COVID-19 a few years ago, sanctions clearly discourage the notion of globalization. Also, just like COVID-19, the Russia-Ukraine war has more countries looking at reshoring and nearshoring with friends and allies.

How will each set of nations react in the future? It’s truly a precarious time, and nobody knows where China and its allies, the U.S. and its allies, nonaligned nations and those involved in the Belt and Road Initiative will end up. The trend toward deglobalization, with pockets of regional globalization, will continue for as long as China threatens to invade Taiwan. Overall, the world economy will continue to be held back until these deglobalization challenges are behind us.

Unfortunately, enterprises and entrepreneurs can only control so much. You can redesign your global supply chain (or, preferably, your digital supply network). You can seek optionality in natural resources, production, logistics, transportation solutions and workforce issues. But returning the world to globalization is a global political problem that must be addressed by global government leaders.

Impacts On Your Supply Chain: A Call to Action

Determining how globalization and deglobalization impact your supply chains and your company is an ongoing process of assessing the costs, risks and benefits of alternative sourcing decisions. This complex globalization/deglobalization evaluation truly never ends. However, it is vital, as it affects every topic covered in this white paper.

From a supply chain perspective, this evaluation impacts resilience, lead times, cost reduction (acquisition cost, transportation costs, customs, tariffs, taxes, inventory costs), quality improvement and customer satisfaction.